I love lush beds of hostas! I love the variety of colors and shapes and sizes and bloom stalks. I love how hardy they are and how little maintenance they need. Unfortunately, our neighborhood deer love them as much as I do. After losing plant after plant to their voracious appetites, I knew I had to figure out some kind of alternative that would keep the deer away and still be an easy care, beautiful and environmentally sound addition to my landscape.

My landscaping conversations with Dan Nelson, lead designer at Embassy Landscape Group,

routinely bring up the idea of basing the design on the concept of plant communities. His philosophy is that using communities of plants results in landscapes that are not just attractive,

but are essential elements of a healthy planet. They consume less of our precious resources and, once established, require minimal day to day maintenance. They complement rather than fight against the natural environment and most importantly, they connect us to a sense of place .

When Dan began talking about plant communities, I thought that they were simply any plants grown in the same bed or location. By my interpretation I thought I was already planting in communities. In my head, my heirloom zinnias, snapdragons and salvia were a community because they were in the same raised bed. It turns out that, although in a very broad sense it seemed that I had created a community (compatible species that cover the ground in interlocking layers ), there is much more to the concept than I realized.

Thomas Rainer and Claudia West, authors of the book Planting In A Post-Wild World contend that there are two different kinds of plant communities — naturally occurring plant communities and designed plant communities.

Describing them in terms of landscape design (since plant communities can be classified in many different ways, ie. physical appearance, structure, physical environment}, naturally occurring communities, or so-called wild communities, are groups of plants that share a common environment and interact with each other, animal populations and the physical environment (Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program).

When most of us think of “nature,” and “naturally occurring”, we hold a static picture in our minds. The forest we picture today looks exactly the same as the one we will picture tomorrow or a month from now. With the exception of the shifting seasons, our mental forest — or mountainside — or grassland — never changes.

In reality though, naturally occurring plant communities are constantly changing; they are fluid. As seeds are blown or carried in by animals, insects and even humans,

new plants form and begin to grow, competing for their share of the available critical natural resources of light, water and nutrients. Other plants die out, perhaps from drought or flood or fire,

or perhaps they simply reach the end of their lifespan.

The natural landscape changes in an ecological succession, sometimes very quickly and sometimes very slowly.

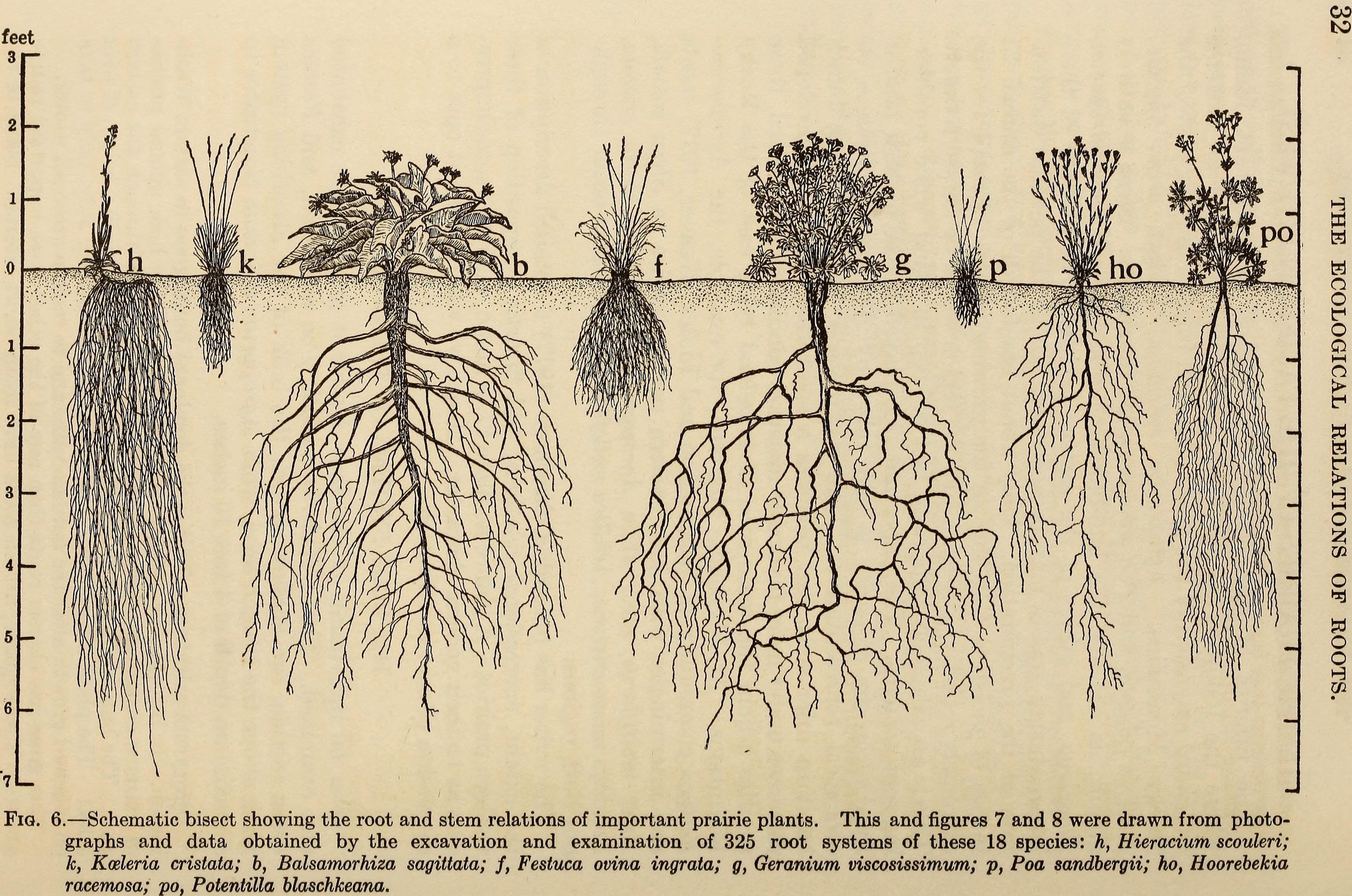

Naturally occurring plant communities are complex, consisting of various types and levels of interactions. Plants in communities both compete with and adapt to one another. Root systems for example, accommodate one another by accessing water and nutrients at different soil levels.

This reduces potentially damaging competition. Each member’s need for light forces accommodations. Species whose growth habit is more upright and narrow and thus require less sunlight flourish next to plants that are shorter but have broader leaf surfaces. Both are able to produce the energy they need to survive without impeding the other.

Designed plant communities, on the other hand, are created to re-interpret nature in response to environmental changes that have occurred over time. We know that human impacts have significantly changed the environment; where meadows, prairies and forests with rich soil once stood, now roads, office parks and neighborhoods fill the space.

Nature itself though, has also changed the environment. Long ago moving glaciers changed the shape and structure of the land, while today fires, floods and hurricanes (to name just a few) do the same.

Designed plant communities therefore allow us to replicate, experience and understand a slice of nature’s past within the confines of the present. Using nature’s palette as a base, designed communities accentuate and emphasize the beauty of a wild plant community while maintaining an order or structure that appeals to the contemporary viewer.

In order to be a true plant community and not just a planting bed, certain conditions must be met. All of the plants must be able to survive, and hopefully flourish within the same environment. Needs for sun, water, soil type etc. must be similar.

A second condition is that the members of the community must work together rather than against one another as they seek water, sunlight and nutrients

Understanding the difference between a planting bed and a plant community is the first step in building “an authentic connection with the landscape that engages our senses and fills us with wonder.” (Planting In A Post-Wild World)

Join us next week as we study the design principles of designing with plant communities. Our focus will be shade gardens. Hope to see you then.